Nomenclature:

Botanical nomenclature is about naming plants. Bear in mind that plant names refer to abstract entities – the collection of all plants (past, present, and future) that belong to the same group. As you will recall, taxonomy is about grouping. Botanical nomenclature is about applying names to taxonomic groups.

Scientific names of plants reflect the taxonomic group to which the plant belongs. One must first decide on the groups to be recognized; only then does one start to be concerned about assigning an appropriate name to the plant. Scientific names are never misleading. No matter where you are, every plants has only one correct name. so long as its taxonomic treatment is not in dispute. This last is a major reservation, but we can ignore it for now. The universality of scientific names means that even English speaking people can find out what species grow in China or Saudi Arabia by reading a technical flora of these countries. Not only are the names the same, they are always written in the Latin alphabet.

Pronunciation: There is as little point about worrying over the ‘correct’ pronunciation of scientific names as there is in worrying over which is the correct pronunciation of English words.

Taxonomy refers to forming groups. Plants that belong to the same group have the same name. The taxonomic decisions concerning how a group is to be treated (what goes in the group, what rank it should be recognized as) MUST be made before it can be assigned a name. It does not matter how you decide what its affinities are (unless, of course, you want others to support and use your treatment), but you must make these decisions before you can decide on an appropriate name for the group. So remember taxonomy first.

If people are going to communicate around the world, there needs to be an internationally accepted system of nomenclature. Creating such a system was not, and is. not, an easy task. It was not until 1930 that agreement was reached on an International Code had become standard around 1753. There were, however, many areas where there was widespread agreement in practice, with some of the practices dating back to before Linnaeus. For reasons that you will learn later, Linnaeus is taken as the starting point for botanical nomenclature. Let’s consider for a moment some of the areas of agreement that existed before there was formal agreement on an International Code of Botanical Nomenclature.

The International Code of Botanical Nomenclature

Principles of Botanical Nomenclature: There are six principles that guide decisions concerning the Code.

1. Uniqueness Principle (Principle IV).

The uniqueness principle states that there is only one correct name for a particular taxonomic group within a given taxonomic treatment. It is the central principle upon which all the remainder of the code is based. If people disagree on the taxonomic treatment, they will consider different names to be correct but, within any treatment, each taxonomic group has only one correct name.

2. Type Principle (Principle II).

The type principle states, “The application of names of taxonomic groups is determined by means of nomenclatural types”. For vascular plants such as grasses, a nomenclatural type is a herbarium specimen that has been deposited in a herbarium. A nomenclatural type anchors the meaning of a name. If there is an argument as to what kind of plant the author of a name meant by a particular name, one examines the type specimen. No matter what taxonomic treatment is followed, the name must be used in a sense that includes its type specimen. If, as occasionally happens, the author of a new name provides a description that does not match the type specimen, it is the type specimen, not the description, that determines what kind of plant is called by the name in question.

Adherence to the type principle did not become mandatory until 1958. Prior to that time, when taxonomists published a new name they frequently simply listed several different specimens exemplified what they meant by the name, without identifying any particular specimen as the ‘top dog’ among the examples. All the designated specimens, including their duplicates, are referred to as syntypes: nomenclatural types of a single name, all of which were equally important. This became a problem if later taxonomists decided that there are two or more taxa among the specimens listed. When this happens, it became necessary to determine which of the specimens listed belongs with the original name.

To prevent such situations arising, the rules for designating a type specimen were made more explicit. Since 1990 it has been necessary to identify the exact specimen that is to be the nomenclatural type of the taxon, and the herbarium in which the specimen is located. Between 1958 and 1990 it was enough to specify who collected the specimen, where it was collected, the date on which it was collected, and the collection number it was given, if any. The problem was that, if the collector made several duplicate specimens, each of the duplicates is a syntype. In most instances this is not a problem, but occasionally the supposed duplicates turn out to belong to different species. Requiring that an author state exactly which of the specimens is to be regarded as the nomenclatural type helps prevent even this kind of problem. If possible, the accession number of the type should be specified as well as the name of the herbarium in which it is located, but many older herbaria do not give their specimens accession numbers.

There are several different kinds of type specimen, but the most important are holotypes, lectotypes, neotypes, and epitypes. The next most important are isotypes, syntypes, and paratypes. The first four kinds of type refer to specimens that are, unequivocally, the nomenclatural type of a name. A holotype is a specimen that has been designated the nomenclatural type of a name by the person creating the name. If the person who originally published a particular name did not designate a holotype, a later taxonomist may select a specimen to serve as the nomenclatural type. This specimen then becomes what is called the lectotype of the name. If the holotype or lectotype is destroyed or lost, a new type specimen can be selected. Such replacement types are called neotypes.

An epitype is a specimen selected to be the nomenclatural type of name for which there is a holotype, lectotype, or neotype available. Why would it be necessary to select another specimen as a nomenclatural type? Sometimes the holotype, lectotype, or neotype simply does not show the features that are needed to determine, unequivocally, to which of two taxa it belongs. In such a case, it cannot be used to fix the meaning of a name. In such situations, another specimen can be selected as the ‘anchoring’ specimen; it is this specimen that is the epitype.

3. Priority Principle (Principle III).

This principle states, in essence, that if a taxonomic group has been given two or more names, the correct name is the first name that meets the Code’s standards for publication. Basically, this means that the priority of a name dates from the time that it was first published and made known to other botanists. Writing the name in a letter (or Email) to a colleague does not count, nor do notes made on herbarium sheets.

Taxonomic groups may end up with two or more names for several reasons. The most common reason is taxonomic disagreement, about which the Code says nothing. Sometimes, the person publishing a later name is simply unaware that the group has already been named. In other cases, two (or more) names were given to different looking specimens of what was later treated. as a single group. Whatever the reason, the priority principle states that only the first name validly and group legitimately published for a particular taxonomic is correct. In determining priority, the date that matters is the date on which the material was actually mailed to other institutions; this is not always the same as the year on the cover of a book or journal.

4. RETROACTIVITY PRINCIPLE (PRINCIPLE VI).

This principle states, “The Rules of nomenclature are retroactive unless expressly limited”. The Retroactivity Principle means that anyone proposing a change in the Code needs to consider the effect that the proposed change will have on names published in a wide range of literature and over a considerable period of time. This is an intimidating requirement. It is why all proposed changes to the Code undergo committee scrutiny before being voted on. If the committee has a problem with a proposed change, one of its members will get in touch with the person proposing the change. The committee member may point out unforeseen consequences of the proposed change. Alternatively, he or she may suggest examples that will make a stronger case for the change, or suggest modifications that will avoid some undesirable consequences.

All proposals to change the Code are published in Taxon, but they remain proposals until they are voted on at the next International Botanical Congress.

5. PRINCIPLES 1 and V.

The other two principles are straightforward. Principle I states that botanical nomenclature is independent of zoological and bacteriological nomenclature. If an organism is considered to be a plant, then it must be named in accordance with the Botanical Code. If it is considered a bacterium, it must be named according to the Bacteriological Code. Similar names for crop plants are given by ICNCP. Principle V states that scientific names are to treated as if they were Latin, regardless of their derivation.

OTHER KEY PROVISIONS OF THE CODE

1. Any changes in the Code should be designed to nincrease the stability of plant nomenclature. No one likes name changes, not even the taxonomists that them.

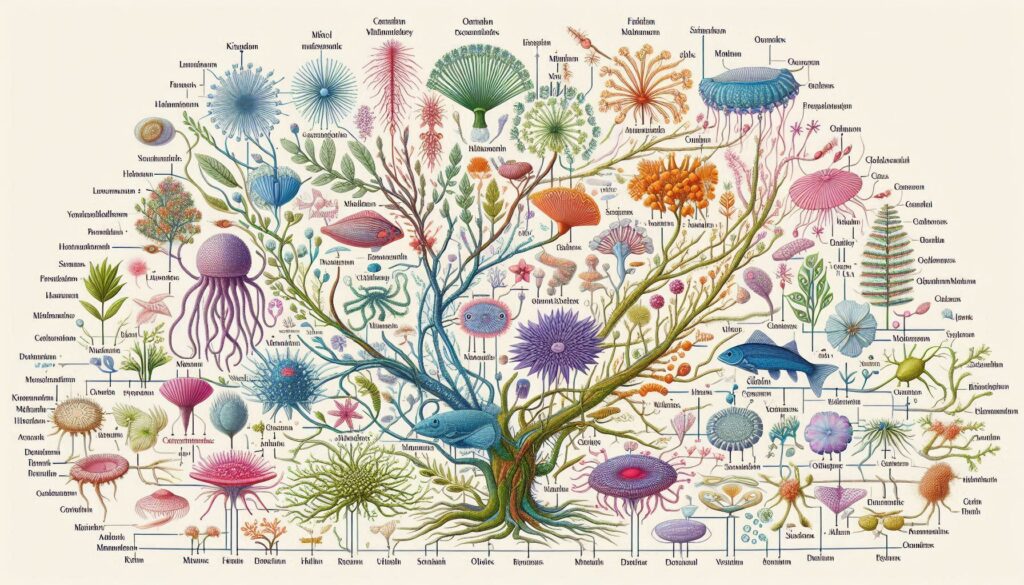

2. Every plant belongs to a species, every species to a genus, every genus to a family, every family to an order,every order to a class, every class to a division (also called a phylum nowadays – a concession to the greater number of zoologists in the world). This is the taxonomic hierarchy. Note that the Code assumes the existence of species. It does NOT state what constitutes a species, let alone discuss whether species are real. The Code also requires that plant diversity be summarized in a hierarchical structure. Again, it is not a question of whether such a structure really exists. The fact that the Code assumes the existence of species and a hierarchical structure does not mean that that the assumptions are correct, merely that, in naming plants (and the zoological code is similar in this regard), one must act as if species are real and nature is hierarchical. Many people object to this, but no one has provided a persuasive argument for dropping the system.

PUBLISHING SCIENTIFIC NAMES.

Before a name, even a name that has a Latin form, can be accepted as a scientific name, it must satisfy several criteria. Some of these have to do with its form, others with how its existence and meaning are made known to others.

Form: Principle V states that a scientific name must be treated as if it were Latin, but the Articles 16-28 of the Code also specify what form the name must take.

| RANK | ENDING | EXAMPLES |

| Division(Phylum) | Phyta | Pinophyta, magnoliophyta |

| Class | opsida | Pinopsida, Liliopsida, Magnoliopsia |

| Order | Ales | Pinales, Liliales, Magnoliales |

| Family | aceae | pinaceae, lilaceae, magnoliaceae |

| Tribe | eae | pineae, lilieae, magnolieae |

| Genus | a noun | pinus, lilium, magnolia |

| Species | depends | pinus flexilis, lilium. Grandiflorum, magnolia grandiflora |

| Variety | depends | pinus flexilis var. Humilus |

Family names must be formed by combining a genericn ame with the suffix aceae, but there are eighte xceptions to this rule. Each of the eight exceptional names was almost universally used, and used in the same sense, throughout the world when the first edition of the Code was prepared and so, in accordance with the overriding goal of achieving nomenclatural stability, it was agreed that they would continue to be used. The eight names are Gramineae (Grass Family, alternative Poaceae) Palmae (Palm Family, alternatively Arecaceae), Cruciferae (Mustard Family, alternatively Brassicaceae), Leguminosae (Pea family, alternatively Fabaceae), Guttiferae (St. John’s Wort Family, alternatively Clusiaceae), Umbelliferae (Carrot Family, alternatively Apiaceae), Labiatae (Mint Family, alternatively Lamiaceae), and Compositae (Daisy Family, alternatively Asteraceae).

The name of a species is ALWAYS a binomial. ‘Grandiflora’ is not the name of a species. It has to be combined with a generic name to form the name of a The word species, as in Magnolia grandiflora. ‘grandiflora’ is what we call the specific epithet. It states which species of Magnolia is under discussion. Specific epithets are often adjectives that describe some attribute of the plant (it helps to learn a little Latin – ‘grandiflora’ means large flowered), but may refer to the habitat of a species (pratensis -of fields, lacustris of lakes, saxicola – of rocky places), the place where the species occurs (chinensis, europaea, canadensis), or a person that is somehow connected to the species (the connection may be remote) – wrightii (referring a single, male person named Wright), wrightiae (referring to a single female person named Wright), wrightorum (refering to 2 or more people, one of whom – and possibly only 1 out of a 100 – was male) or wrightarum (referring to 2 or more people with not even one male among them – the Romans were sexist).

Technically speaking, subspecies is a higher rank than variety. A subspecies may include several varieties. In practice, most taxonomists nowadays use one rank or the other, but not both. Europeans tend to use subspecies and expect subspecies to occupy somewhat different areas whereas Americans use variety to denote plants that are different from the plants first put in the species. ranks are used almost In practice, the two interchangeably.

Writing Scientific Names: In North America it customary to write names at the rank of genus and below in italics or some other font that sets them apart from the rest of the text. The most recent edition of the Code recommends that all scientific names, no matter what their rank, be in a different font from the rest of the text. Either practice makes it easy to scan for taxonomic information.

The names of all ranks from subgenus up MUST be capitalized. In most instances, the specific epithet – and epithets for lower rankings, must NOT be capitalized. There are some exceptions to this rule, cases where it is permissible, but not required, to capitalize the specific or varietal epithet, but you need to be careful. Personally I recommend always using lower case for epithets (names distinguishing species and lower ranks). That way one is never wrong.

Authorities: You will notice that scientific names are often followed by a word or a capital letter and a period, or one or more unintelligible (to the uninitiated) sets of letters. To join the initiated, read on.

The letters and/or words that follow a scientific name (sometimes they may be within a name – more on that later) are a shorthand reference to the name of the person or person that first gave a name to the entity involved and, in some instances, to the person of persons who first treated it at the rank being used. This is probably easier to understand through some examples. Consider Oryzopsis exigua Thurber

Note that only the first two words are italicized. This means you are looking at the name of a species. ‘Thurber’ is the last name of the person who first gave a name to this species – and the name he gave to it is the one shown. Consider “Oryzopsis asperifolia Michx.”

Again, you are looking at the name of a species in the genus Oryzopsis. This species was first named by a fellow whose name is abbreviated to Michx. The period tells you that his name has been abbreviated. His full name was Michaux. To whom do you think “L.” refers to in “Triticum aestivum L.”? “Dichanthelium lanuginosum (Elliott) Gould”

The name is Dichanthelium lanuginosum. As you immediately recognize (because the name is a binomial), the entity being named is being treated as a species. The first person to give a name to this species was a chap whose last name was Elliott, but he named it Panicum lanuginsoum. An inner circle of initiates could tell you that Elliott refers to Walter Elliott, who lived from 1803 to 1887, in eastern North America (There is a book called Authors of Plant Names that provides such insight).

“Gould” stands for Frank W. Gould came along later and decided that, although Elliott was right in describing the species, he should have put it in a different genus, the genus Dichanthelium. Elliott’s name is in parentheses to show that he was the first person to say “Aha, these plants are different” Gould’s name is outside the parentheses because he said, yes, Elliott was right – these plants are different – but they should be included in the genus Dichanthelium, not Panicum Consider “Distichlis spicata (L.) Greene. Linnaeus [L. stands for Linnaeus] first described the entity, but as Uniola spicata, not Distichlis spicata. Greene was the first person to say no, these plants should be in Distichlis and then publish the combination “Distichlis spicata”. Linnaeus gets credit for being the first person to describe the entity, Green for being the person to give it the name shown.

Most journals, and consequently many professors, ask that you cite the authorities for a name when it is first used. It is a rather meaningless exercise. It is meant to say “I am using this name in the sense that it was used by Greene (in the last example)”, but really you are probably using it in the sense that it is used in some flora – or based on what your boss told you. The 1999 Congress encouraged editors to be more rational about when it was useful to cite authorities and when not, but I suspect that most journals will continue to require them for some time to come.

PROPOSING A NEW NAME OR NEW COMBINATION

If you have to publish a new name or combination, the Code requires that you follow certain rules (which it calls articles). The key requirements are that:

- The new name or combination be published in a normal botanical outlet (not the Herald Journal or Statesman), copies of which are sent to at least two botanical institutions.

- If the name is for a new taxon, the distinguishing characteristics of the taxon, and preferably a full description, must be given in Latin and a holotype Specifid.

- If the name is simply a new combination, genus to another or its demotion to a subspecies, there must be a clear and complete reference to the place where the original name was first published.